Tamara Moats stands beside a painting by an American master and asks a deceptively simple question:

“What do you see?”

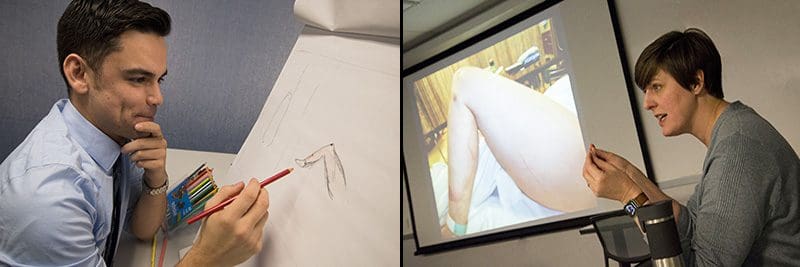

A group of students leans in, eyeing the egg tempera paint of Andrew Wyeth’s “Brown Swiss.” It’s week eight of MED 556, aka Visual Thinking: How to Observe in Depth.

The students are at the Seattle Art Museum to do just that.

They focus first on color. Brittany Christensen, a second-year med student, notes the various shades of brown that dominate the painting, along with some blues, blacks and yellows. The conversation then shifts to discrete objects – a weathered house, a small pond, an empty bench – before ending in the abstract.

“I don’t see smoke coming out of the chimneys,” observes Lucy Liu, another second-year. “Does anyone live here?”

In a few minutes, the painting has moved from a morass of brown color to a haunting landscape of absence. The scene is a good snapshot of MED 556 in action, said Moats, a history teacher at the Bush School and co-instructor of the class. For 10 weeks students practice “Visual Thinking Strategies (VTS),” an approach to learning that encourages collaboration, close observation and conclusions backed by evidence.

By improving their observation skills in the museum, said co-instructor Dr. Andrea Kalus, the students will hopefully sharpen their diagnostic chops in the exam room.

“Doctors have three fundamental strategies in the exam room: observe the patient, touch the patient, listen to the patient,” said Kalus, associate professor of dermatology. “We do a lot of teaching on how to touch the body and how to use a stethoscope, but there’s really no established method to teach someone how to observe. So why not go to a field like art that’s all about the visual to borrow some teaching methods?”

Moats and Kalus have been doing that for 10 years through MED 556, which is co-sponsored by the Henry Art Gallery and supported by Friends of the UW School of Medicine. UW was one of the first medical schools in the country to use VTS, which has become increasingly popular. Several peer-reviewed studies have suggested that students who study VTS do improve their ability to make accurate observations.

Kalus, who complements the course’s museum outings by teaching three sessions involving medical images, is a believer.

“Medicine is very fast-paced. I sometimes feel like I’m on a treadmill when I see patients all day in the clinic,” she said. “This class helps me know when to go slow in a particular moment because I might miss something.”

This semester’s students also seem to have learned the lesson. Liu gave her final presentation on a work by Van Gogh, a frenetic image of a dancehall in France. At first, Liu said, she saw little more than chaos. Then she broke it down into distinct elements – the VTS method in practice — and the scene started to make sense.

She also drew some clear parallels between examining art and examining a patient or an X-ray.

“In medicine, we often make snap judgments about what’s abnormal versus normal. With art, I make snap judgments about whether something is interesting or not,” Liu said. “But when you use these exercises of observation, you think about what makes a painting uninteresting – maybe you prefer fine lines to impressionistic techniques. In medicine, we need to think about how to describe normal.”

Exactly, Kalus told her.

“What you’re developing in this course is the skill of interpretations supported by evidence,” Kalus said. “When you say a scan looks normal, we hope you can say ‘here’s why.’ And that will be because you systematically broke things down and observed.”

Guest Writer: Jake Siegel