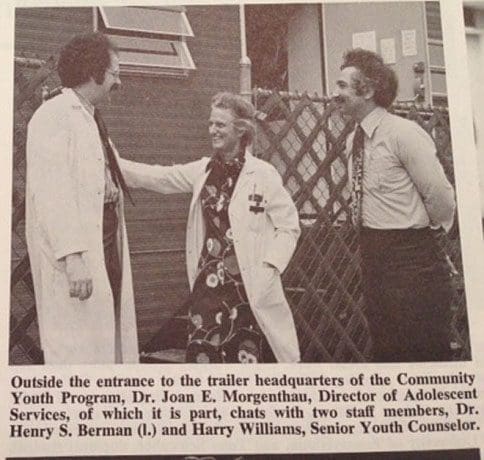

Henry Berman began his career in adolescent medicine at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York in 1971.

“One day, one of my patients ran into our clinic, scissors raised high, screaming, ‘I’m going to kill Dr. Berman.’ I hid in an office until she calmed down. The next day she happened to be sitting next to one of our nurses on a bus and said, ‘I had a bad day yesterday, I tried to kill Dr. Berman.’”

In “Teens and Their Doctors,” Berman and co-author Hannah Dashefsky describe the early years of the field from the opening of the first Adolescents’ Unit at Boston Children’s Hospital in 1951 to the creation of the Society for Adolescent Medicine in 1968. We learn about a group of medical pioneers who understood the unique needs of teenagers. We discover how the cultural and sexual revolution of the 1960s increased the need for free clinics, drug treatment programs, birth control and abortion choices. We read stories — like the one at Mount Sinai — that are “hard to believe unless you were there.”

Berman is a UW Clinical Professor of Pediatrics and an adolescent behavioral health specialist at Seattle Children’s. He spoke about his book and career in a recent interview.

Q: How did you become interested in adolescent medicine?

A: In 1968, I was a pediatrician in the U.S. Army and stationed in Karlsruhe, Germany. Many of my patients were teenagers, either soldiers or dependents of military families. I had an easy way of relating with them. One day, I attended a lecture by C. Henry Kempe, one of the pioneers in adolescent medicine. He said, “Whenever I give this talk, one person in the audience goes into the field.” In the instant, I knew that I would be that person.

Q: Are teenagers different today than in the past?

A: The path from childhood to adulthood is characterized by a number of tasks. Adolescents need to begin the process of separating themselves from their parents, develop a sense of sexuality, focus on friends and begin to get a sense of their place in the world. They also lay the foundation for supporting themselves.

Most of these tasks are in our DNA, so they are unchanged. But job opportunities today are different. Fifty years ago, boys did not need a college degree to have good jobs in construction, auto repair, welding, factories and manufacturing. They could support a family on their salary. However, since 1970, the number of blue-collar jobs as well as jobs in manufacturing have decreased by two-thirds. Boys in high school are not likely to see opportunities to support themselves in those areas, so they are likely to plan to attend college even if it does not suit them. As a result, they have a much higher dropout rate than girls.

There is now a group of what I call “lost boys.” In the last ten years, most of the boys in my practice have little practical career direction. Because this is Seattle, they would like to invent video games.

Girls are doing much better. Many have plans to go to college and start careers with good salaries.

Q: What other changes are you seeing in your patient population?

A: Eating disorders are much more common; they increased in the 1980s and remain at that level. Forty percent of our adolescent clinic visits at Seattle Children’s are for eating disorders, which are very difficult and complex. We are now seeing more males with eating disorders because of social media. These boys are trying to look like male youth who are shown online with a flat abdomen. But it’s not a healthy look.

Another change is that transgender youth have come out of hiding. A few years ago, we thought it was perhaps one out of every 2,000 kids. Now that it’s more open, the number is clearly much higher.

Q: What is the secret to working with teenagers?

A: It comes down to understanding, listening, caring and communicating that you care. You need to gain teenagers’ trust. If you don’t gain their trust, they won’t tell you anything. If they share something personal and you react in a judgmental way, they won’t tell you again — because now you’re like their parents. If they don’t trust you because you didn’t listen to them or didn’t make them feel you cared, they are not likely to follow your recommendations.

When we listen with understanding and show we care, we become their “secure anchors.” For example, four years after seeing me, one of my patients was facing a difficult challenge in college. She knew she could call me, and I helped her work through the issue.

Q: Why did the girl at Mount Sinai want to kill you?

A: She felt betrayed. She thought I knew that a friend had died in the hospital and had not told her. Dr. Joan Morgenthau was my mentor at Mount Sinai and one of the great pioneers in the field. She did not think it was safe for me to see this girl again. But I felt bad for her and would have continued being her doctor.

Q: In Teens and Their Doctors, you describe the birth of adolescent medicine. What do you see as its future?

A: There are 40 million adolescents in the United States and only 1,200 members of the Society of Adolescent Health and Medicine. We need to extend our reach through consultations and trainings with pediatricians and family medicine doctors to help them improve health for all adolescents.