Raise your hand if you picked up a pandemic hobby. For many of us this looked like baking, collecting plants or sewing masks.

But Sina Gharib, MD, a pulmonary, critical care and sleep medicine specialist at the Chest Clinic and Sleep Medicine Center at Harborview, took on something much more massive in scale: astrophotography.

Comet Leonard (C/2021 A1) captured at Skygems Observatory, Namibia on Dec. 30, 2021. The raw data were processed by Sina Gharib to construct the final image.

The sky is the limit

In his career, Gharib has always aimed high. As an internal medicine resident, he knew he wanted to pursue pulmonary medicine because of how central it is to life itself. (We don’t survive very long if we’re not breathing, after all.)

“It is a field where you have to know everything about how the body works; it’s not just focused on one specific component,” he explains.

During his fellowship he did rotations in sleep medicine and became fascinated with how sleep affects the whole body, just as breathing does. He also loved how collaborative sleep medicine is, bringing together pulmonologists like him as well as neurologists, psychiatrists, surgeons and more.

While his career has been shaped by his own interests, it’s also possible fate was involved. His namesake is Ibn Sina (called Avicenna by Westerners), a famed Persian philosopher and physician who lived from 980-1037 during the Islamic Golden Age.

“He described the pulmonary circulation system before Western physicians did,” Gharib says.

Another fateful fact? Ibn Sina was also an astronomer.

Stargazing from Shiraz to Seattle

Growing up in Shiraz, Iran, the night sky awed Gharib. During the war with Iraq, cities would go dark at night to prevent aerial bomb threats. While this was undoubtedly a scary situation, Gharib used it as an opportunity to admire the stars without light pollution.

“I remember seeing a huge meteor shower once that was incredibly bright. It sparked my interest,” he says.

When the pandemic hit and Dr. Gharib found himself spending more time at home, he decided to finally pursue his interest in the night sky.

He started in his backyard, connecting an 11-year-old camera to his telescope. His first images weren’t great, so he studied up on how to make them better and says his background in physics and engineering proved helpful with this.

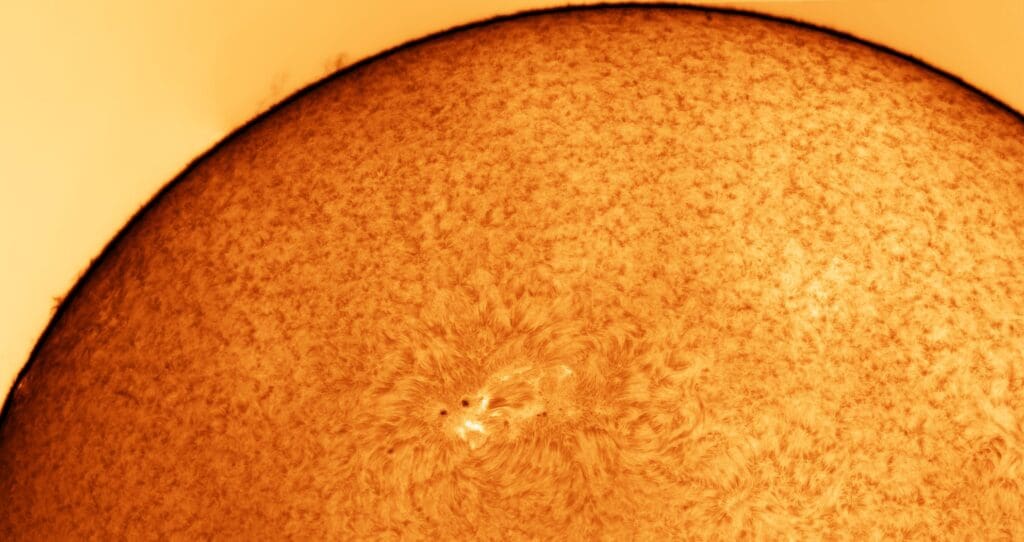

Light pollution is not an issue when taking photos of the sun (taken on Feb. 6, 2022), but a special filter known as hydrogen-alpha is needed to limit the sunlight to a specific wavelength.

Large bright objects can be readily photographed from the backyard. This image of the first quarter Moon was taken by Gharib on March 10, 2022 from his backyard.

By now you may be wondering: How can someone do astrophotography in an area as cloudy as Seattle? The answer is: only on clear nights. Dr. Gharib still enjoys going into his backyard when the weather is good and photographing the sun, moon, planets and bright nebulae, but for shots of faint objects deeper in space, he has had to find a different strategy.

It’s a high-tech marvel: Gharib can remotely access a telescope in Namibia to take photos of deep-space objects such as comets and galaxies. Clear skies and no light pollution make for some powerful images.

Two images of the majestic Orion and Running Man nebulae taken by Dr. Gharib using a remote observatory (top) and from his own backyard in Queen Anne (bottom).

Processing the shot, processing the pandemic

If you’re thinking astrophotography seems pretty complicated, you’re right.

“It’s not just taking a picture. You have to take many pictures of the object of interest because they’re very faint,” Gharib explains.

The exposure (the amount of time light hits the camera’s digital sensor) is significantly longer than in other types of photography, too. Some shots may need exposures of a few minutes whereas others may need hours of total exposure.

Then there’s the processing. Gharib has to sort through all the images and combine them in a way that accurately represents the space object while also reflecting his own vision.

“A lot of the colors are there but the way they’re presented is personal. None of the images from Hubble that you see are actually how they look if you look through the telescope; the colors are much fainter and the image is much blurrier,” he says.

Astrophotography hasn’t just taught Dr. Gharib how to process possibly thousands of images and turn them into a single showstopper, it’s also given him time and space to reflect on the past years in the pandemic.

“It makes me appreciate what I have and puts life into perspective. I’m less stressed or concerned about small things. The images from some galaxies are millions of light years away, so what we’re seeing is looking back into history in some ways. It makes me appreciate the vastness of space and puts into perspective our troubles and difficulties, which in the big picture aren’t really a big deal. We’re not the center of the universe,” Gharib says.

The light from the Sombrero galaxy takes almost 30 million years to reach Earth. The Helix nebula, sometimes called “Eye of God” is comprised of remnant gases from a dying star that can be seen in the center and is destined to become a white dwarf.