Highlights | New Surgical Treatment for MALS

- Median arcuate ligament syndrome (MALS) is difficult to identify and frequently misdiagnosed.

- Open vascular surgery offers better results than the traditional laparoscopic procedure.

- A multidisciplinary approach can help patients achieve complete symptom relief.

Three years ago, a patient in her 20s with median arcuate ligament syndrome (MALS) sat in the office of UW Medicine vascular surgeon Benjamin Starnes, MD, FACS. Her symptoms were classic, and CT imaging confirmed her diagnosis. The next step seemed simple — Starnes recommended the patient see a gastric and esophageal surgeon for laparoscopic surgery.

That’s when the patient burst into tears. She already had that referral, but everything she’d read online from the nationwide support group MALS Pals indicated that open vascular surgery to access the aorta directly was more effective. She’d come to Starnes seeking that alternative, and after a discussion, he agreed to perform the procedure.

“This patient had lost 25 pounds unintentionally. She would lie in bed all day, and it hurt to eat,” says Starnes, chief of the division of vascular surgery at UW Medicine. “Taking on her surgery was simple for me because I operate on the aorta every day.”

Her open vascular surgery eliminated the patient’s symptoms and launched Starnes — and UW Medicine — down an unexpected path. Today, MALS referrals account for a large portion of his practice. Since that first surgery, he’s received 115 referrals, operated on nearly 50 patients and established the institution as a go-to destination for MALS relief.

Diagnosing a misunderstood condition

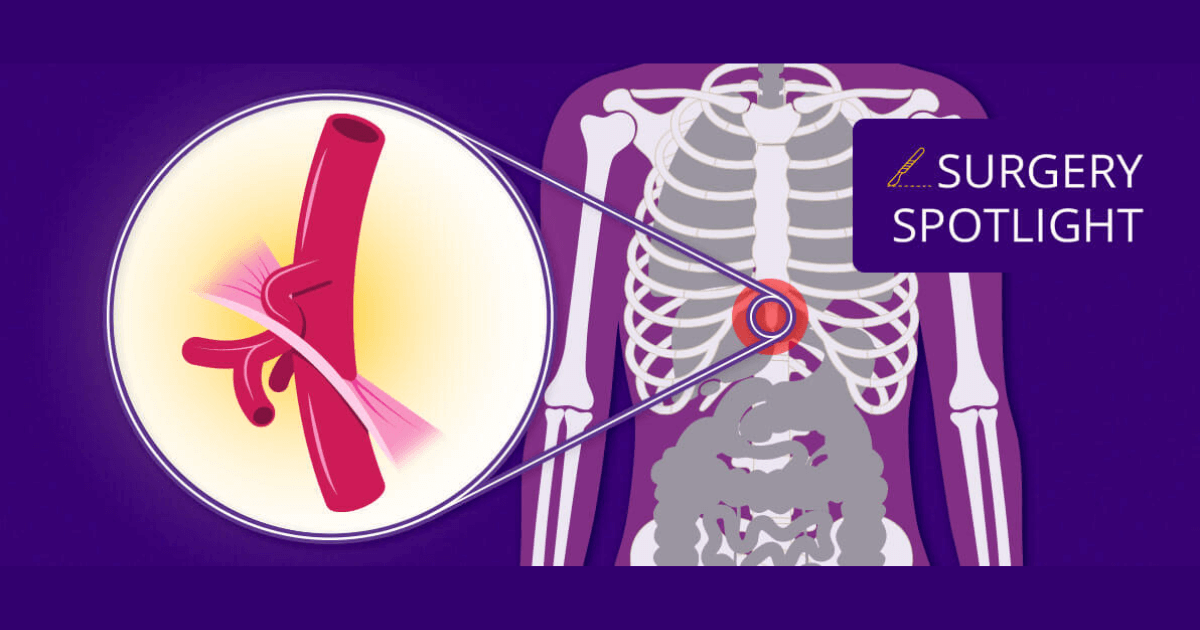

As a nerve compression syndrome, MALS develops when the median arcuate ligament in the chest puts too much pressure on the celiac artery, which delivers blood to the stomach, liver and other organs. It’s difficult to diagnose because symptoms, including pain immediately after eating, nausea, hypertension and shortness of breath, are often confused with other conditions.

“Often, people will be told they have indigestion, inflammatory bowel disease or problems with their gallbladder,” Starnes says. “Some are even told they have eating disorders or that the problem is all in their head.”

An incomplete treatment

MALS is rare, affecting only two in every 100,000 people. Most patients are women in their 20s and 30s. And without treatment, they can die of malnutrition and starvation.

For years, the first-line MALS treatment was a laparoscopic procedure with a general surgeon. It’s a minimally invasive procedure designed to relieve the pressure caused by the median arcuate ligament, but, Starnes says, it largely falls short.

Truly alleviating MALS symptoms requires both dividing the ligament and removing the damaged nerves around the aorta and celiac artery. And doing so with a laparoscopic technique is challenging.

“General surgeons hesitate to do the necessary perivascular dissection because they don’t want bleeding that covers the camera and blocks their vision. Bleeding can also create an urgent need to pivot to an open procedure quickly,” he says. “With a laparoscopic procedure, they can’t really get close to the celiac artery, so they don’t do the complete surgery.”

As a result, he says, only 30% of patients treated laparoscopically have symptom relief longer than 12 months.

A new surgical approach

Starnes takes a different approach to offer patients a better long-term outcome — and a potential cure. He performs open vascular surgery even though it’s a more involved procedure that leaves patients with a scar between the navel and breastbone.

“With open surgery, I have direct contact with and can touch the aorta,” he says. “It gives me better access to the ligament and the nerves. Plus, if needed, I can control any bleeding with a quick little stitch.”

With a multidisciplinary team of gastroenterologists and interventional radiologists, Starnes identifies patients with MALS using a celiac plexus block. This procedure uses CT guidance to deliver a pain-relieving injection of bupivacaine and steroids. If symptoms decrease after the injection, the patient will likely have a good outcome after surgery.

The surgery itself is straightforward. First, Starnes makes a midline incision between the breastbone and navel to expose the diaphragm and aorta. Next, he locates and divides the median arcuate ligament to reduce pressure on the celiac artery. Then, he removes the damaged nerves around the artery that trigger the pain, applies a steroid (typically methylprednisolone) and closes the incision.

Most patients experience immediate symptom relief, he says. His team also connects patients with psychiatrists to address the anxiety that frequently accompanies coping with MALS symptoms over time.

Learning more about MALS

Not only is MALS difficult to diagnose, but it is also widely misunderstood. Most textbooks incorrectly describe it as a vascular condition rather than a nerve compression problem, Starnes says. Consequently, there’s a need for more education and research.

Starnes and his colleagues have created awareness videos and educational materials, with $150,000 raised by a former 17-year-old MALS patient and her family. These educational tools can help both patients and providers better understand this condition.

In the coming months, Starnes would like to collaborate with investigators at UW Medicine and other institutions to further explore this condition through:

Studies that measure how quickly electrical impulses move through gastric nerves

Evaluations of T-cell receptors to detect aspects of MALS that may trigger or impair the immune system

Histopathologic examinations of tissue specimens

Overall, he says, UW Medicine is a trailblazer in advancing treatments for MALS. It’s also the ideal institution to unearth valuable information about this life-threatening condition.

“We are here to learn about rare conditions. We innovate and develop new treatment methods,” Starnes says. “We’re changing the perceptions behind why MALS happens, and we’re only at the beginning of this journey to understand more about this syndrome.”