HIGHLIGHTS | Combining medicine and technology

- The ConnectAbility Lab was created in 2018.

- The lab’s advisory board includes healthcare professionals, tech companies and patients.

- In the lab, people with spinal cord injuries can learn about new assistive technology and practice using devices like smart home speakers and virtual reality.

-

In 2018, Deborah Crane, MD, secured grant funding from the Craig H. Neilsen Foundation to create an assistive technology facility at Harborview Medical Center. Together, Crane, Amy Noonan, OTR/L, CSRS, Leslie Fox, OTR/L, and an interdisciplinary team launched the ConnectAbility Lab.

Today, the lab is a high-tech wonderland where people with spinal cord injuries and other mobility impairments can learn to use the latest accessible technologies, like adaptive gaming, virtual reality and alternative communication.

Creating the lab

Noonan and Fox knew the power of technology could help patients with spinal cord injuries find independence and connect with their loved ones.

The patients who come to Harborview with spinal cord injuries — many of whom come from out of state — often arrive with phones that were broken in their accident. Without a phone, these individuals aren’t able to easily contact friends and family members who can’t make it to the hospital.

Other patients who have been living with spinal cord injuries for a while may not know about the latest accessibility features on their phones and tablets or the new technology that can help them communicate and complete daily tasks.

Enter the ConnectAbility Lab.

With this new assistive technology lab, Noonan and Fox created a space for patients with spinal cord injuries to explore cutting-edge rehabilitation technology that can help improve their quality of life and increase their independence.

For inpatients whose injuries prevent them from physically accessing the lab, Noonan and Fox purchased seven new mobile units that are outfitted with phones, tablets, wireless speakers and alternative switches. This increase in mobile units allows Noonan and Fox to leave the carts with patients so that they can use the devices at any time.

“Before I’d show up with a tablet and then I’d have to take it out of the room,” Noonan says. “It’s good to leave it with a patient so they can continue to practice using technology or play a game to take their mind off of things or FaceTime to keep in touch with friends and family while they’re in the hospital.”

For one of Noonan’s patients, whose husband lives too far away to regularly visit, the additional access to a phone and tablet means the patient can contact her husband. Noonan set up voice control on her phone and taught the woman how to use this technology so that she could make and receive calls without needing the help of a nurse.

“Technology is so prevalent and accessible right now; everyone has a smart phone or a tablet. With minimal additional equipment, we can give someone who has no ability to move their arms and legs — in five minutes — the ability to use their smart phone,” Noonan says. “That’s where our life is for most of us.”

Connecting with the tech community

A unique feature of the ConnectAbility Lab is its assistive technology advisory board, which is made up of healthcare professionals, individuals with spinal cord injuries and experience with assistive technology, and local tech companies like Amazon, Microsoft and Google.

“We wanted to get the ear of big tech giants to see where consumer technology is headed and help teach them to make it more accessible on the back end,” Fox says.

By learning about the lived experiences of people with spinal cord injuries — and the way these individuals currently use technology to problem solve — medical and technology professionals are able to reimagine solutions. Together, the board develops better assistive devices and collaborates on creative ways to utilize technology that is already in the market.

One such device? Adaptive gaming.

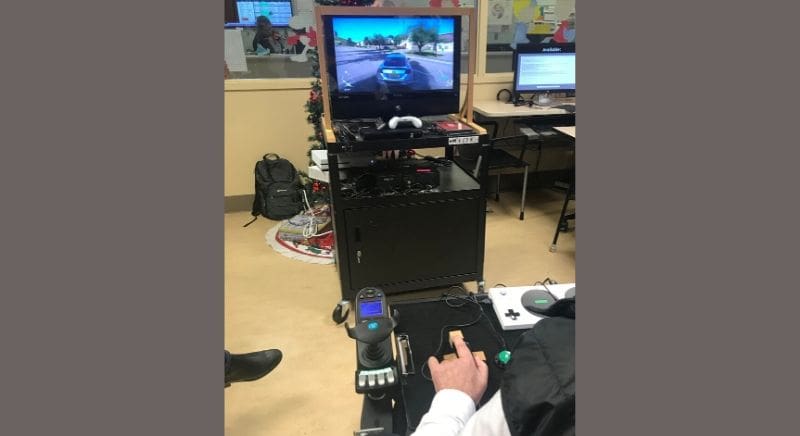

Serendipitous timing led to Microsoft launching its new accessible controller just as Noonan and Fox created the advisory board. Since then, the board’s Microsoft contact has hosted adaptive game nights, where anyone can learn how to use alternative controllers to play Xbox games.

And when the CEO of a local virtual reality (VR) company joined the board, he began experimenting with how to make virtual reality more accessible for individuals who can’t hold controllers or turn their head — even inviting them to try out different options in the company’s VR lab.

“The advisory board has the potential to impact technology development on a broad scale at a time when consumer technology is rapidly evolving,” Fox says. “Instead of trying to hack existing technology to work for someone with limited mobility, we want emerging technology to be inherently accessible and affordable.”

Man playing an adaptive video game.

Increasing independence

In the lab, equipment ranges from everyday devices to specialized controls.

Patients can learn how to adjust the settings already on their phones and tablets to make the devices accessible, or they can practice turning on a TV and changing the temperature with the lab’s smart home devices and speakers — both cost-effective ways that technology can be implemented to make daily tasks easier.

The lab’s 3D printer can also cheaply print adaptive devices and writing tools for people to use.

“My favorite thing about technology is we can so rapidly give people some independence back. Every initial introduction to equipment is really exciting,” Noonan says.

More specialized equipment includes the sip and puff, which allows users to navigate a joystick with their mouth and select by sipping and puffing; gyroscopic glasses that let users move a curser around by moving their head; and eye control that allows users to write text and move a mouse by tracking eye movement.

This variety enables people to play around with how they input to their device so they can find what works best for them, whether it’s using their breath, eyes, head, foot or mouth.

Improving therapeutic options

Virtual reality, which is still rapidly developing, not only provides entertainment, but can also teach people how to sit up on their own, balance, reach further and move their arms up.

A large proportion of people with spinal cord injuries are men 17 to 22 years old and for many of these individuals, adaptive gaming is particularly useful in boosting morale and aiding with therapy.

“I can encourage them to get out of bed to play a video game, and secretly I’m strengthening their arms to drive a wheelchair,” Noonan says. “It’s a great therapy tool as well as a return to meaningful interaction.”

Whether people are learning how to open and lock their doors through a smart home assistant, surf the web or call a friend, the ConnectAbility Lab creates community and empowers people with spinal cord injuries to have more control over how they engage with the world.

“Technology has really been a solution for people with spinal cord injury where medicine has not,” Fox says. “It provides a workaround for doing what you want to do.”

Editor’s Note: this article was edited to add Deborah Crane on April 16, 2020.